|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

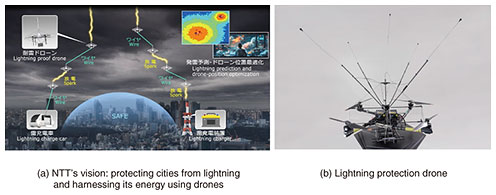

Feature Articles: Creating Innovative Next-generation Energy Technologies Vol. 23, No. 12, pp. 33–39, Dec. 2025. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202512fa3 Lightning Control and Charging Technologies that Protect People and Equipment and Harness EnergyAbstractAt NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories, we have greatly advanced technologies that protect communication facilities from lightning. We are now conducting research on lightning control and lightning charging technologies that will eliminate lightning strikes on critical infrastructure and cities, while also harnessing lightning as a source of energy. This article introduces our drone-based experiments to trigger and guide natural lightning, as well as experiments to generate compressed air that stores lightning energy by using lightning surge currents. Keywords: lightning, drone, lightning charging 1. IntroductionLightning is one of the world’s natural phenomena that has long been a cause of serious harm to humans. Benjamin Franklin’s 1752 kite experiment that proved lightning is a form of electrical discharge is well known. From ancient times to the present, many studies have sought to find ways to prevent lightning damage; thus, various lightning countermeasures have been implemented in today’s critical facilities, including the NTT Group’s communication infrastructure. Nevertheless, it is difficult to implement perfect countermeasures for the enormous number of facilities worldwide, and lightning damage has not been eliminated. The annual economic loss to Japan alone is estimated to be on the order of 100 to 200 billion yen [1]. In response to this state of affairs, NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories has decisively shifted its focus away from conventional countermeasures that assume lightning strikes will occur toward developing lightning control technologies that eliminate lightning strikes. Lightning control technology means inducing lightning at intended locations and timings under thunderclouds, capturing the generated lightning, and guiding it to a safe place. The goal is to reduce lightning strikes on critical facilities to as close to zero as possible. Rather than simply releasing the induced lightning to ground, we are also studying lightning charging technologies to make effective use of its energy. This article introduces the latest research on lightning control technologies using drones (Fig. 1(a)) and lightning charging technologies. For the drone-based lightning control technologies, we describe the development of drones with lightning tolerance (lightning protection drones), capabilities to intentionally trigger lightning and safely guide it, and the results of demonstration experiments in which such drones were flown beneath actual thunderclouds. As an example of foundational work on lightning charging, we also present investigations of a method for converting lightning energy into compressed air for storage by using lightning surge currents. 2. Status of research on lightning control using dronesA variety of approaches have been studied for intentionally triggering and guiding lightning. The best-known is rocket-triggered lightning, in which a grounded wire is launched by rocket at high speed to heights of several hundred meters. This method has achieved many successful records and has contributed to research on lightning generation mechanisms and lightning protection [2]. There have also been reports of successful laser-triggered lightning, where a high-powered laser is irradiated into the air to create plasma that acts as a conductive path guiding lightning [3]. However, various issues arise when these methods are applied to protecting critical facilities and cities: the places where they can be implemented are limited and their mobility is poor. Rocket-triggered lightning uses gunpowder, which entails strict safety management, and if triggering fails, the launched rocket and wire may fall back to the ground, limiting applicable sites. Laser-triggered lightning requires bulky laser equipment that is difficult to transport. To efficiently protect many critical facilities from lightning that occurs at different locations depending on date and time, we need a method with high flexibility regarding the possible locations in which it can be implemented, while moving in step with the motion of thunderclouds. To address these issues, NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories is studying drone-triggered lightning for lightning control involving drones that fly over important buildings, facilities, and urban areas [4]. To achieve lightning control using drones, the drone in question must continue flying without failure or malfunction even if it is struck directly by lightning. To achieve a high probability of protection for important buildings and facilities in the future, the system must actively induce lightning to the drone. Therefore, we are studying two key technologies: (i) lightning protection technology for drones so that the drone does not malfunction or fail even when directly struck, and (ii) an electric-field-based lightning triggering technology to intentionally trigger lightning at the drone’s location. To demonstrate these component technologies, we conducted proof-of-concept experiments in which a lightning protection drone was flown beneath real thunderclouds to induce and guide lightning. 2.1 Lightning protection technology for dronesWhile conventional aircraft incorporate measures against lightning and are designed to continue flying even when struck, drones are generally not intended to fly in severe weather and have much smaller payloads than aircraft, so they typically have no lightning protection. If a drone is directly struck by lightning, a malfunction or damage is expected, including a crash-landing. We therefore devised a design method for a lightning-protection cage that can be mounted on off-the-shelf drones and prevent malfunctions or failures even when lightning directly hits the drone. As shown in Fig. 1(b), the lightning protection drone uses a lightning cage made of lightweight yet robust aluminum pipes. When the drone is directly struck, the large current is diverted into the metallic conductors of the cage so that lightning current does not flow through the drone’s body. Increasing the number of aluminum pipes reduces the lightning surge current flowing in each individual pipe, which helps mitigate deterioration of or damage to the cage. By distributing the lightning radially, strong magnetic fields generated by the large current cancel each other, reducing magnetic effects on the drone.

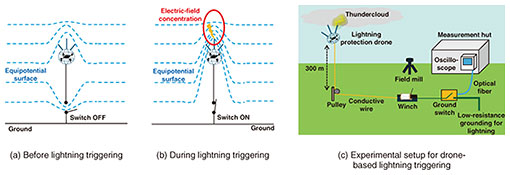

To verify robustness during lightning, we applied artificial lightning to a prototype lightning protection drone. Even when a 150-kA artificial lightning pulse (a level of electrical power that exceeds that of more than 98% of natural strike currents and is over five times the natural average) was applied, we confirmed that no failures or malfunctions occurred in the drone. 2.2 Electric-field-based lightning triggering technologyFlying a lightning protection drone beneath thunderclouds while it is connected to ground with a wire creates a “flying lightning rod” that provides a lightning protection effect. However, the area protected with this method alone is limited in size. To protect a wider area, we consider it important to be able to actively induce lightning at the drone’s location, successively neutralizing charges in the thundercloud, thus preventing lightning elsewhere. To actively induce lightning, we devised a method for changing the electric-field strength around the drone by placing a switch in the conductive wire between the airborne drone and ground and toggling it ON/OFF. As a thundercloud approaches and the ambient electric field increases, connecting the hovering drone to the ground by turning the switch ON at the optimal moment instantly causes the drone and the earth to become equipotential, and the electric field around the drone rises sharply. A discharge thus occurs between the drone and thundercloud, which is expected to promote lightning initiation (Figs. 2(a), (b)). 2.3 Demonstration experiment for lightning protection technology for drones and electric-field-based lightning triggering technologyTo demonstrate the lightning protection technology for drones and electric-field-based lightning triggering technology, we conducted drone-triggered lightning experiments during December 2024 and January 2025 at an elevation of 900 m in the mountains of Hamada City, Shimane Prefecture, Japan. We chose Shimane because the Sea of Japan side of the country, including this particular region, is one of the rare areas in the world where lightning frequently occurs in winter. Winter thunderclouds are lower than summer counterparts, so the distance between the flying drone and thundercloud is shorter, providing a favorable environment for drone-triggered lightning experiments. We continuously monitored the electric field generated by nearby thunderclouds using an instrument called a field mill*, and when the ambient electric field increased as the clouds approached, we flew the lightning protection drone and attempted to induce lightning. Figure 2(c) shows the experimental setup. The lightning cage of the drone was connected to a ground-based trigger switch with a conductive wire. To prevent the wire from being blown sideways by strong winds during flight, a motorized winch was used to keep the wire always tensioned and allow for remote take-up. The trigger switch could be toggled ON/OFF remotely and was designed to withstand the high voltages expected across its terminals when thunderclouds were nearby. Currents and voltages at the trigger switch and electric-field strength observed by the field mill were measured simultaneously with oscilloscopes in the instrument hut, so that waveforms before and after lightning initiation to the drone could be confirmed.

Considering the safety of personnel and instrumentation, we conducted experiments from inside an instrument hut and a work vehicle when thunderclouds were nearby. We used optical fiber cables for measuring currents, voltages, and electric fields and a lightning-resistant transformer to supply power to the instrument hut so that, even if lightning struck it, our measuring instruments, or the nearby power lines, the lightning current would be prevented from entering the hut. On December 13, 2024, when thunderclouds approached, we flew the wired lightning protection drone to an altitude of 300 m and, by remotely turning the ground trigger switch ON, connected the drone to earth potential. Immediately thereafter, we observed a sharp cracking sound and light emission both in the thundercloud near the drone and at the ground winch (Fig. 3(a)). Measured data indicated that a large current flowed through the wire at the same time as the sound and light, and that the ambient electric field changed markedly (Fig. 3(b)). From these results, we confirmed that our switch operation intentionally triggered a lightning discharge. Although the tip of the air terminal (lightning rod) at the top of the lightning cage sustained some damage (Fig. 3(c)), the drone body experienced no failures or malfunctions, the cage suffered no damage, and the drone maintained stable flight.

These results confirm the world’s first success in drone-triggered lightning. This demonstrates in principle that it is possible to protect critical facilities from lightning using drones.

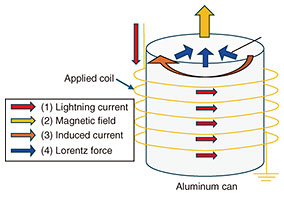

3. Status of research on lightning charging technologiesFor lightning guided to intended locations using drones, we are examining methods for effectively harnessing it as energy. However, lightning is a phenomenon in which extremely large currents of hundreds of kiloamperes flow in less than one millisecond, making charging existing batteries impossible. Charging using capacitors—devices with fast response—has also been proposed, but to withstand the large currents and high voltages that accompany them, an enormous number of capacitors must be connected in parallel and series, and each element must be controlled to prevent explosion, resulting in extremely high cost [5]. We are therefore researching technologies that can convert the electrical energy of lightning into other forms of energy for storage. As one example of our basic studies, we present the status of investigations into a method for converting lightning energy into compressed air [6] for storage. 3.1 Fundamental study of lightning charging using compressed airWe examined a method for generating compressed air using lightning in which a metal can is compressed by electromagnetic induction accompanying a lightning surge. The principle is shown in Fig. 4. (1) A lightning surge current is applied to a coil that has a metal can placed inside. (2) A magnetic field is generated inside the coil. (3) An induced current flows on the surface of the metal can in the opposite direction to that of the lightning surge current. (4) The magnetic field and induced current produce an inward Lorentz force on the can, causing it to collapse; thus, compressed air is created inside the sealed can. The generated compressed air is stored using a high-pressure-rated tank. By opening the valve at any desired time, the stored compressed air can drive a turbine, generating electricity. We introduce the results of fundamental tests using artificial lightning surges to generate compressed air.

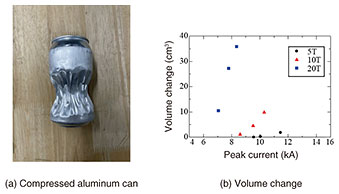

3.2 Feasibility confirmation of lightning charging using compressed airTo determine whether compressed air can be generated using lightning energy and verify the correlation between applied current and amount of compression, we conducted experiments using a lightning surge tester. We fed a lightning impulse current (8/20 μs) into the drive coil and measured the change in volume of an aluminum can placed inside the coil to confirm whether compressed air was generated. We applied voltages of 25, 27.5, and 30 kV and used drive coils with 5, 10, and 20 turns. To quantify the amount of compressed air, we measured the change in volume before and after surge application by filling the inside of the aluminum can with water. Our results using this setup indicate that the aluminum cans were compressed as shown in Fig. 5(a) when the surge was applied, confirming that compressed air can be generated by a lightning surge current. Figure 5(b) plots peak current versus change in volume; the change in volume was proportional to the peak current, and we confirmed that increasing the number of coil turns yielded larger volume changes even at lower peak currents. Since the amount of compressed air increased proportionally with applied current, these results indicate that conversion to compressed air is a valid approach for storing lightning energy.

4. Conclusion and future workThis article presented progress at NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories on lightning control technologies aimed at eliminating lightning strikes on critical infrastructure and cities, and on lightning charging technologies that harnesses lightning energy. With experiments under actual thunderclouds, we achieved the world’s first success in inducing and guiding lightning using a drone and demonstrated that our lightning protection drones can withstand natural lightning. For lightning charging, we confirmed the feasibility of converting lightning energy from electrical into another form of energy for storage, and specifically into compressed air. Going forward, for lightning control we will accelerate R&D toward practical systems that protect critical facilities from lightning using drones, while advancing (i) lightning induction, (ii) lightning guidance, and (iii) lightning prediction. For (i) lightning induction, improving the success rate is essential for practical use. We will therefore quantitatively analyze the sequence of events that occurs immediately after turning ON the ground potential switch during induction—making use of electromagnetic and fluid simulations—to elucidate the conditions for successful induction. In parallel, we will continue to accumulate successful experimental cases and extract success conditions using an inductive approach. For (ii) lightning guidance, we will pursue further research on lightning-cage design to achieve drones with an even higher lightning tolerance and work with external organizations to address hardware issues expected in practical deployment, such as handling conductive wires and automating drone operations (takeoff/landing, charging/battery replacement, wire attachment). For (iii) lightning prediction, we will research methods for predicting the location and timing of lightning with pinpoint spatiotemporal accuracy. For lightning charging, we will continue to study the compressed-air approach currently under investigation and explore methods for storing charge more efficiently for our future use of lightning energy. References

|

|||||||||||||||