|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Feature Articles: Creating Innovative Next-generation Energy Technologies Vol. 23, No. 12, pp. 46–51, Dec. 2025. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202512fa5 Toward Fusion Energy—Integrating Knowledge through AI and Data ScienceAbstractFusion energy is expected to be a clean, safe, and sustainable energy source. However, it requires stable confinement and precise real-time control of ultra-high-temperature plasma. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and data science provide new tools for addressing these challenges. NTT has developed two methods: AI-based magnetic equilibrium prediction using a Mixture of Experts model, which achieved centimeter-level accuracy on the JT-60SA tokamak in collaboration with the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, and sparse modeling for estimating mathematical models directly from plasma data. Together, these methods accelerate fusion research and contribute to future energy innovation. Keywords: fusion energy, AI, data science 1. IntroductionEnergy is a foundation of modern society, yet most electricity and energy consumed today still rely on fossil fuels such as oil and coal. Climate change and resource depletion have become pressing global challenges, creating the need for sustainable alternatives. Fusion*1, the same reaction that powers the Sun, has emerged as a promising candidate for next-generation energy. Fusion occurs when light atomic nuclei combine to form heavier nuclei, releasing enormous amounts of energy. Unlike nuclear fission, it does not produce explosive chain reactions or significant radioactive waste, and is therefore regarded as a clean, safe, and sustainable source of energy. Fusion has gained international attention alongside renewable energy as a means of combatting global warming and achieving carbon neutrality. Japan has been a leader in this field for decades. In March 2024, the Japan Fusion Energy Council (J-Fusion) was established to promote collaboration among industry, academia, and government, with the aim of demonstrating power generation in the 2030s and commercial reactors after 2050. NTT has joined this national effort by contributing its expertise in information science. NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories, in partnership with the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST), is investigating how artificial intelligence (AI) and data science can be combined with plasma*2 physics to create innovative control methods for fusion [1].

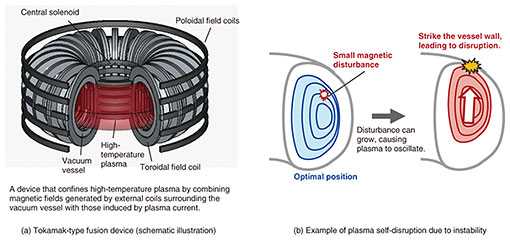

2. AI-based magnetic equilibrium predictionTokamak*3-type fusion devices confine plasma in a toroidal vacuum vessel using magnetic fields, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). Because plasma is inherently unstable, precise control is essential to prevent displacements that could damage the device (Fig. 1(b)). Particles in plasma at around 100 million degrees Celsius travel at nearly 900,000 meters per second, which means the plasma state must be estimated and controlled within milliseconds. Since high-temperature plasma does not emit visible light, its state cannot be measured directly with cameras. Instead, magnetic sensors*4 surrounding the vessel detect the strength and direction of magnetic fields as electrical signals, which are then used to reconstruct the plasma boundary and shape.

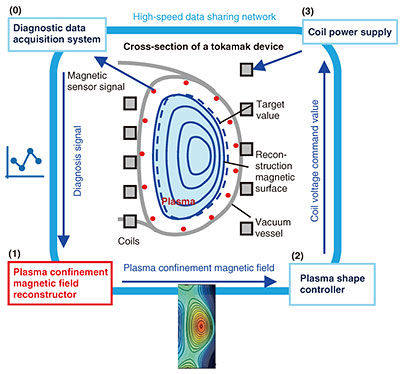

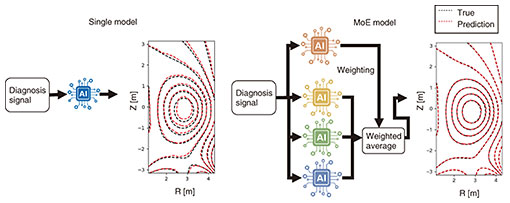

Traditional reconstructions of magnetic equilibrium*5 are based on plasma physics equations such as Maxwell’s laws. While accurate, these calculations can take hundreds of milliseconds, whereas plasma states may change in just several milliseconds. As a result, real-time control*6 systems often approximate only external magnetic fields, even though information about internal profiles is essential for stability analysis. To address this limitation, we apply AI-based reconstruction [2]. Once trained, AI can learn direct mappings from sensor signals to equilibria and predict the plasma state in a single forward computation (Fig. 2). Early attempts using a single neural network achieved reasonable performance under steady-state conditions but lacked accuracy during dynamic changes. To improve robustness, we introduced a Mixture of Experts (MoE)*7 model, in which multiple neural networks are trained under different operating conditions, and a gating network dynamically selects the most suitable experts for each situation.

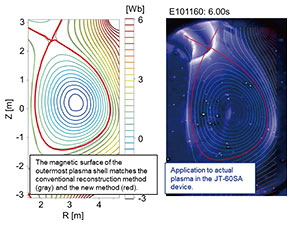

We applied this MoE model to JT-60SA*8, one of the world’s largest tokamak devices operated by QST in Naka, Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. As shown in Fig. 3, MoE predictions (red contours) closely match reference equilibria (black contours), while single-network predictions show noticeable deviations. In fact, MoE reconstructions reproduced plasma position and shape with an error of about one centimeter, even though the plasma radius extends several meters. This accuracy is a world-first achievement for AI-based equilibrium prediction. An example of error reduction is illustrated in Fig. 4. MoE is not limited to plasma boundaries; it can potentially reconstruct internal current and pressure profiles, enabling predictive detection of instabilities and proactive control strategies.

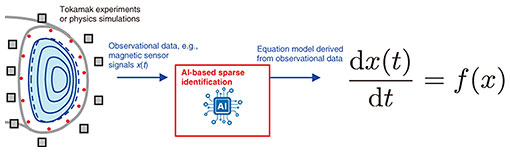

3. Knowledge discovery through sparse modelingWhile AI predictions offer speed and accuracy, they are often treated as black boxes, making it difficult to interpret physical meaning. For fusion research, interpretable models are important both for advancing understanding of plasma dynamics and for designing reliable controllers. Sparse modeling*9, a data science technique that explains phenomena using only a small number of essential terms, addresses this need. We apply a method known as sparse identification*10, with which it is assumed that plasma dynamics can be represented by a differential equation composed of only a few active terms. From experimental data such as temperature and density, we build a library of candidate functions and apply sparse regression to select the minimal set of terms that best describes the observations. To further enhance reliability, we introduce the oracle property*11, which ensures that with sufficient data the correct model structure can be recovered while eliminating unnecessary terms. By combining sparse identification with the oracle property, we extract concise and physically meaningful models from experimental data. When applied to plasma diagnostics, this approach has produced simplified equations that capture essential dynamics while maintaining predictive accuracy. These models are computationally efficient and easy to interpret since each term has physical significance. They also enable real-time controls: equations can be updated continuously from streaming data, allowing for short-term forecasting of plasma behavior and use in feedback control. This workflow is illustrated in Fig. 5. Beyond supporting control, such models provide opportunities to compare with established theories, validate hypotheses, and discover new physical insights.

4. Conclusion and prospectsFusion is expected to play a central role in achieving a clean, safe, and sustainable energy society, yet its implementation requires overcoming the formidable challenge of precisely controlling ultra-high-temperature plasma in real time. At NTT Space Environment and Energy Laboratories, in collaboration with QST, we are addressing this challenge by applying AI and data science. We introduced two methods: AI-based magnetic equilibrium prediction, which has demonstrated centimeter-level accuracy on the JT-60SA tokamak, and sparse modeling, which derives concise and interpretable governing equations directly from plasma data. These methods highlight the complementary strengths of physics-based models, AI, and data-driven techniques. Physics provides consistency and reliability, AI enables rapid adaptability, and sparse modeling offers interpretability and structure. By integrating these strengths, fusion research can advance toward both practical control and deeper scientific understanding. Future work will expand these methods to wider operating regimes, including uncertainty quantification, and apply them to real-time systems for large-scale experimental devices. Beyond plasma physics, interdisciplinary collaboration across energy engineering, control theory, and data science will be essential for creating the technological foundations of a clean and sustainable energy society. References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||