|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

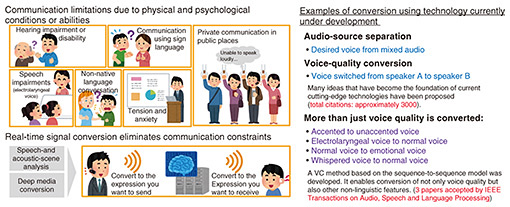

Front-line Researchers Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 1–7, Jan. 2026. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202601fr1  Augmenting Communication Capabilities with Cutting-edge Voice-conversion Technology that Enables Users to Freely Customize the Impression of Their VoiceAbstractCommunication is subject to a variety of constraints arising from physical and psychological conditions and ability as determined by, for example, disabilities, age-related decline, and the challenges of speaking an unfamiliar language. To address these limitations, increasing attention is being directed toward communication-function augmentation technologies, which convert a speaker’s voice in real time to one better suited to the situation, thus removing barriers to effective interaction. Dr. Hirokazu Kameoka, a senior distinguished researcher at NTT Communication Science Laboratories, has long been engaged in research not only on transforming voice quality but also on enabling prosodic modifications such as accent conversion, whisper-to-speech conversion, and electrolaryngeal-to-speech conversion. To meet emerging demands such as creating a “cute” or “tough” voice, he has also begun exploring technologies that enable the subjective impression of speech to be freely manipulated. We asked Dr. Kameoka to look back on his past research achievements, share the current status and concrete outcomes of his latest original projects, and discuss his broader approach to research. Keywords: voice conversion, sequence-to-sequence model, diffusion model We are one of the first to incorporate technologies used in other fields, such as image generation, into voice-conversion methods and engage in highly original research—Would you tell us about your current research on voice-conversion methods? With our (NTT Communication Science Laboratories) goal of how to augment communication capabilities in mind, I’m researching machine learning and signal processing, specifically, voice conversion (VC). In a broad sense, VC is the process of inputting one voice and outputting another voice and includes tasks such as separating a mixed audio source and replacing the voice quality (namely, voice tone) of one person with that of another person. In addition to replacing voice quality, VC includes conversion of speech accent and conversion from an electrolaryngeal voice to a normal voice (for people who can no longer speak on their own). I’m also researching converting emotionless voices into expressive ones (Fig. 1). We’ve proposed many cutting-edge ideas on the topic of VC, and I’ll introduce some of them in more detail.

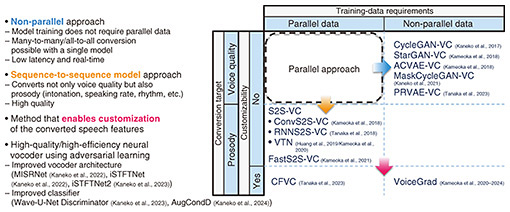

VC is generally achieved by first learning a transformation function (or conversion model) for speech features using training data then applying this model to an input speech signal. As shown in Fig. 2, research on VC can be broadly classified from two perspectives. The first concerns the nature of the data required for training, distinguishing between parallel and non-parallel approaches.

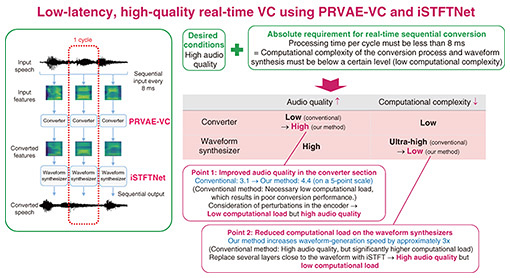

The parallel approach refers to training a VC model using pairs of utterances (parallel data), in which different speakers read the same sentences. For example, a pair of “hello” utterances is created by two different speakers uttering “hello.” If a sufficient amount of parallel data can be collected, this approach can produce highly accurate conversion models. However, collecting parallel data is costly and labor-intensive, posing a significant practical limitation. To overcome this limitation, the non-parallel approach was proposed. This approach makes it possible to train VC models even from arbitrary speech data that are not matched on a sentence basis in the manner of the parallel approach. When we first began researching VC, the parallel approach was mainstream. However, inspired by the emerging interest in unpaired style transfer in the image domain at the time, we conceived the idea that a similar approach could be applied to VC and subsequently proposed a series of non-parallel methods. Typical examples include Cycle-GAN-VC and StarGAN-VC. PRVAE-VC—proposed by a member of my team—has been attracting attention. The second perspective of classification concerns whether the target of conversion is limited to voice quality or extended to a broader range of voice characteristics. Many conventional VC methods are focused exclusively on voice quality, namely, the timbre associated with a particular speaker. In contrast to these methods, the sequence-to-sequence model approach makes it possible to convert not only voice quality but also non-linguistic characteristics such as prosody and accent. Prosody includes intonation and rhythmic patterns, encompassing expressive qualities such as emotion, speaking style, and individual habits of speech. Features such as English accent and pronunciation style fall outside the domain of simple voice quality and considered broader speech attributes. Conventional methods have limitations in regard to converting these characteristics, so I felt a new approach was necessary. To address this challenge, we turned our attention to sequence-to-sequence models, which were gaining significant traction at the time in speech recognition and machine translation. Although the application of such models to VC was virtually unexplored then, we proposed one of the first approaches based on this framework and demonstrated that using this framework makes it possible to convert prosody in addition to voice quality. A direction we have recently been focusing on is developing methods for enabling the characteristics of the converted speech to be flexibly customized. With most conventional methods, the target of conversion is predetermined, and corresponding training data have to be collected and prepared before building a conversion model. However, in actual usage scenarios, a variety of requests for the desired voice arise according to the situation. In the case that no conversion model meets these requests, it is necessary to devise a method for combining trained models to achieve flexible conversion according to the usage scenario. It was from this perspective that we developed VoiceGrad, the world’s first VC method based on diffusion models. Another important point concerning VC is the process of generating speech waveforms after feature conversion. This generation process has a direct impact on both latency in real-time systems and the ultimate audio quality. Therefore, in parallel with our research on conversion models, we have also been advancing research on designing architectures capable of fast and high-quality speech generation. This series of studies has been carried out as a collaborative project with Nagoya University and Tokyo Metropolitan University over a five-year period until the end of fiscal year 2024. This project was selected for CREST (Core Research for Evolutionary Science and Technology) funded by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), which enabled researchers with diverse expertise to come together under shared and clearly defined research goals and engage in in-depth, multifaceted discussions. By accepting many students from the partner universities as interns, we were able to advance our research efficiently. I believe that the fact that each member was able to pursue their research with a common awareness of the issues under this collaborative setup was a major success of this project. —By combining PRVAE-VC, a non-parallel method, with iSTFTNet, an improved neural vocoder, you achieved low-latency, high-quality, real-time VC, correct? The process of generating speech waveforms from speech features is conducted using a neural vocoder. WaveNet, which appeared around 2017, attracted much attention due to its exceptionally high audio quality; however, the enormous computational time required for generating waveforms led to considerable discussion among speech researchers about its applicability to real-time applications. Over the next eight years or so, research on model compression and acceleration advanced rapidly, to achieve faster generation while preserving audio quality, and has also become one of our most-important research topics. Regarding real-time VC, delays are almost unacceptable, and even slight weight reduction can have a significant effect. Speech can be divided into the smallest units called phonemes, the average duration of which is said to be approximately 100 ms. If your voice returns to your ears with a delay of more than 100 ms, the perceived phonemes will differ from the phonemes actually spoken, and that difference will result in a discrepancy in auditory feedback. This discrepancy is known to confuse the brain, and speech production becomes significantly more difficult. With that knowledge in mind, we aim to process speech well below 100 ms, namely, within 50 ms. A neural vocoder called HiFi-GAN has become widely used as a high-quality, low-latency waveform generator. However, it remains challenging to complete waveform generation with HiFi-GAN within 50 ms using standard computational resources. In contrast, two years ago, our team proposed iSTFTNet and demonstrated that it can generate waveforms within 50 ms. By combining iSTFTNet with the above-mentioned non-parallel method PRVAE-VC, we achieved low-latency, high-quality real-time VC (Fig. 3). For reference, samples of speech converted by the combination of iSTFTNet and PRVAE-VC are included in references [1] to [3]. This work was exhibited as a new real-time VC technology at NTT Communication Science Laboratories Open House [4] and NTT R&D Forum, where it attracted much attention.

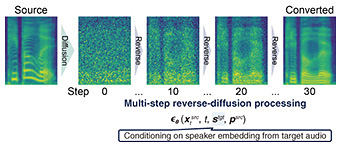

—VoiceGrad, which makes it possible to freely customize the impression of a voice, is an exciting method to look forward to in the future. We first proposed (and published in a preprint) VoiceGrad, a diffusion-model-based voice conversion method, in 2020. In 2024, it was finally published in a journal, and we are now conducting diverse research on the basis of this foundation. While diffusion models are now widely known, especially in the field of image generation, VoiceGrad was the first method to apply diffusion models to VC (Fig. 4). At the time we proposed VoiceGrad, generative adversarial networks (GANs) were mainstream in image generation, and diffusion models had not yet attracted the attention they do today. However, when I first encountered the idea of diffusion models, I intuitively understood their power and was convinced that it could definitely be applied to VC. This conviction led us to adopt such models ahead of others.

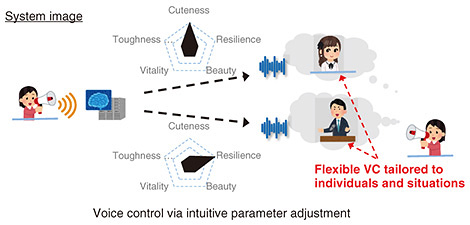

What I found particularly compelling at that time was that diffusion models treat image and audio generation as a type of optimization problem. In optimization, one typically minimizes (or maximizes) an objective function, but by introducing auxiliary objectives (secondary loss terms), one can guide the solution to satisfy multiple goals simultaneously. This method is a type of regularization, and I thought that with diffusion-based approaches, this regularization method could enable highly flexible and customizable VC, making it possible to tailor the converted voice to a user’s specific preferences. For example, if a user desires a “cuter” or “tougher” voice, it is possible to convert the user’s voice to one that meets the user’s needs while retaining the characteristics of the user’s voice. In other words, by designing multiple objective functions that represent different requirements and optimizing them simultaneously, it is possible to achieve VC that satisfies multiple requirements in a coherent manner (Fig. 5).

When we first began investigating VoiceGrad, I assumed that the conversion target would be limited to voice quality in a manner similar to conventional non-parallel methods. However, as our research progressed, it became clear that VoiceGrad possesses capabilities similar to sequence-to-sequence-based conversion models, enabling not only voice-quality modification but also flexible manipulation of prosodic features. I therefore believe that VoiceGrad is distinct from the non-parallel methods based on GANs and variational autoencoders that we have previously proposed. Recent research has also confirmed that improvements to VoiceGrad can also enable conversion of English accents. This new finding demonstrates the great potential of VoiceGrad. At this time, I only have samples of voice-quality conversion; however, if the reader is interested in the conversion performance of VoiceGrad, I encourage readers to listen to the samples given in a previous study [5]. VoiceGrad is a promising VC method. Achieving that promise is an interesting technical challenge—What are your future prospects? As mentioned above, VoiceGrad has many advantages, which include being a non-parallel method, being able to convert not only voice quality but also prosodic features, and having a high degree of customizability and excellent conversion performance. I’m therefore currently positioning the development of VoiceGrad as an important direction for future research. At the same time, technical challenges are becoming apparent, the most important of which is achieving low-latency real-time processing. The current architecture of VoiceGrad is non-causal in signal-processing terms, which inevitably introduces delays because it relies on future input information. To achieve real-time VC, however, a causal structure, i.e., a method that uses only information input before a certain point in time when converting speech at that point in time, is necessary. All conventional non-parallel methods listed in the upper right of Fig. 2 satisfy this causal requirement and capable of low-latency real-time processing. However, VoiceGrad currently relies on a non-causal formulation that requires future inputs, which remains a key limitation. In view of this challenge, developing a causal variant of VoiceGrad constitutes my next research topic. Another issue is that early versions of VoiceGrad required iterative computation, requiring a significant amount of computational time. Although these requirements are major technical challenges that we currently need to overcome, they are also very interesting research topics. I believe that once these challenges are overcome, VoiceGrad will open up even greater possibilities. One such attempt is FastVoiceGrad. While FastVoiceGrad still retains a non-causal structure, it has become clear that it can shorten the process that previously required multiple iterations to a single step without compromising audio quality. We are now extending this line of research by incorporating causal constraints, and promising experimental results have begun to emerge, giving us increasing confidence in the feasibility of real-time VoiceGrad. It is important to connect the dots and fill in the space—What do you keep in mind on a daily basis as a researcher? I believe—and constantly remind myself—that knowledge and experience should not be treated as individual points; instead, they must be connected with lines. It is not easy to fill a space simply by scattering points across it. However, by connecting those points with lines, we can expand our understanding efficiently and fill the entire space. In other words, I believe that researchers should not stop when they have acquired certain knowledge; instead, they should relate that new knowledge to existing knowledge and develop their understanding into something more general and universal. This mindset resonates with the learning principles of neural networks. Neural networks are so powerful because, rather than simply memorizing individual learning samples, they can interpolate multiple samples and learn from samples that do not exist, as if they existed. I have always felt that when researchers incorporate diverse knowledge and experience in a similar way to that of neural networks, the way they connect this information and systematize it into a universal understanding is fundamentally important. New research results, including those concerning artificial intelligence, are being announced every day. Rather than dismissing them as simply “interesting,” we must consciously connect them with the knowledge we have accumulated thus far; consequently, our understanding will be elevated to something more universal and profound. I believe that it is vital that we maintain this mindset during our research activities. References

■Interviewee profileHirokazu Kameoka received a B.E., M.S., and Ph.D. from the University of Tokyo in 2002, 2004, and 2007. He is currently a senior distinguished researcher and senior research scientist with NTT Communication Science Laboratories and an adjunct associate professor with the National Institute of Informatics. From 2011 to 2016, he was an adjunct associate professor with the University of Tokyo. His research interests include audio and speech processing and machine learning. He has been an associate editor for the IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing since 2015 and member of the IEEE Audio and Acoustic Signal Processing Technical Committee since 2017. |

|||||||||||