|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

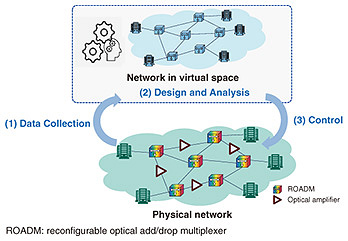

Feature Articles: High-value-added Transmission Technologies through the Convergence of Optical and Wireless Technologies for IOWN/6G Research and Development of Optical-network Digital-twin Technology for On-demand Optical Network ServicesAbstractThe Innovative Optical and Wireless Network (IOWN) All-Photonics Network (APN) provides communication with ultra-large capacity, ultra-low latency, and ultra-low power consumption by transmitting optical signals without electrical signal conversion and is now expected to enable fully on-demand services. To achieve this, autonomous network operation is essential. NTT is working toward this goal by creating a digital twin of the optical network; the optical network is reconstructed in a virtual space to automate design, analysis, and control. This article introduces our efforts to support on-demand optical services, with a focus on the technology for automatic optical-path provisioning. Keywords: IOWN APN, digital twin, automatic optical-path provisioning 1. IOWN APN and optical-network digital twin1.1 On-demand optical network services via IOWN APNThe Innovative Optical and Wireless Network (IOWN) All-Photonics Network (APN) directly connects customer sites and devices via optical wavelength paths*1, and signals are transmitted entirely in optical form without converting them into electrical signals along the way. This enables communication services with ultra-large capacity, ultra-low latency, and ultra-low power consumption. IOWN APN is expected to enable an on-demand optical network service that can rapidly establish optical wavelength paths between various locations according to user requirements, delivering the required bandwidth, to the required place, at the required time. A representative use case is distributed datacenters. By using the high-capacity, low-latency APN to connect geographically distributed datacenters, they can be operated as if they were a single massive datacenter. To provide such services, network resources must be combined with computing resources. Therefore, the APN is being developed not as a stand-alone network service but in combination with a computing infrastructure. 1.2 Operational autonomy through optical-network digital twinTo enable on-demand optical services through the APN, autonomous network operation is essential. Although optical networks are not entirely managed manually, many critical tasks, such as design, analysis, and control, still rely on human intervention. This dependence imposes limits on provisioning frequency and delays in service activation, making it challenging to achieve truly on-demand services. To address this, we are working toward autonomous operation by leveraging an optical-network digital twin. This digital twin collects data from actual network devices and constructs a precise network model in a virtual space. Design and analysis are executed on this virtual network, and optimal control decisions are derived and applied to the real network. This mechanism consists of three continuous steps: (1) Data Collection, (2) Design and Analysis, and (3) Control. Continuously repeating these steps yields autonomous operation (Fig. 1).

This article focuses on technologies related to step (2) and introduces our automatic optical-path provisioning technology.

2. Automatic optical-path provisioning2.1 Operational modes for optical pathsAn operational mode refers to a combination of settings that determine how an optical transmission device sends optical signals. It consists of parameters such as

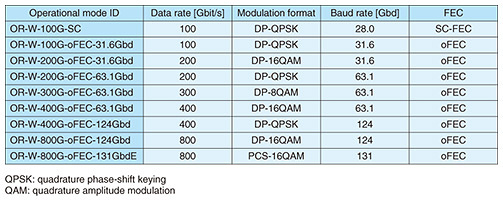

Each operational mode has different characteristics in terms of data rate and transmission feasibility. Table 1 shows a selection of operational modes defined and studied by the OpenROADM Multi-Source Agreement (MSA)*5 [1]. Even this partial list demonstrates the large number of available modes. In addition to OpenROADM MSA, other standardization bodies, such as OpenZR+ MSA*6, as well as vendor-specific implementations, define their own operational modes. Since optical transmission devices support multiple operational modes, it is crucial to select the appropriate mode on the basis of the current state of the optical network.

2.2 Challenges in operational mode selectionDetermining whether a signal can be transmitted without error using a given operational mode is not straightforward. This is because two factors must be considered simultaneously:

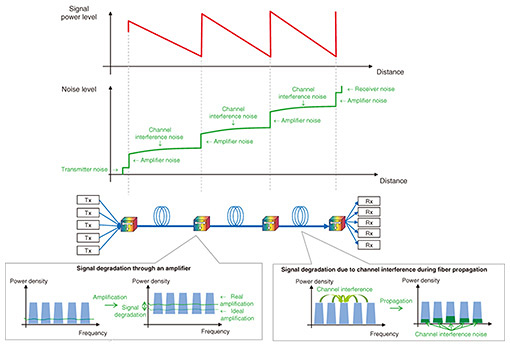

In a simple optical link without amplifiers, signal degradation is mainly caused by optical power attenuation, which can be roughly estimated on the basis of transmission distance. However, in real large-scale networks, signals are relayed and amplified using optical amplifiers, making it insufficient to assess transmission feasibility based solely on optical power (Fig. 2, top). Although amplifiers boost the signal, they also introduce noise at each stage, gradually degrading the signal (Fig. 2, bottom left). Therefore, it is essential to account for the amount of signal degradation (noise). Amplifiers are not the only source of noise. Other factors, such as the internal circuitry of transceivers (TRxes) and adjacent channel interference in wavelength-division multiplexing (Fig. 2, bottom right), also contribute to signal degradation. In short, accurately understanding the total noise generated across the transmission system is crucial (Fig. 2, top).

Each operational mode has a different level of noise tolerance. Even with the same amount of noise, some modes may be feasible while others may not. For example, as the modulation level*7 increases, the distance between symbols becomes smaller, reducing noise tolerance. While higher modulation levels increase data rates, they also introduce a trade-off between data rate and transmission distance. Thus, selecting an appropriate operational mode requires addressing two key challenges: (i) accurately estimating the total noise generated by the transmission system and (ii) understanding the noise tolerance of each operational mode. We explain methods for estimating the noise level generated within the transmission systems, which is essential for optimal operational-mode selection. 2.3 Estimating major sources’ noise levelsIn transmission systems covering distances from datacenter interconnects to metro-scale networks (up to several hundred kilometers), the dominant noise sources are known to be

These three types of noise can be treated as independent Gaussian noise sources. Therefore, each can be estimated separately then summed up to obtain the total noise level of the transmission system. In this section, we explain how to estimate the noise levels of these three major noise sources. In particular, we introduce NTT’s method for quantifying TRx noise, along with a simplified approach for obtaining it. 2.3.1 ASE noiseASE noise generated with optical amplifiers can be measured directly using an optical spectrum analyzer or calculated from the amplifier’s performance parameters. ASE noise occurs because light spontaneously emitted inside the optical amplifier is amplified, degrading signal quality (Fig. 2, bottom left). The amount of ASE noise can be directly measured using an optical spectrum analyzer to compare the optical spectrum before and after amplification. Alternatively, it can be calculated on the basis of the amplifier’s noise figure, along with the input signal’s optical power and frequency. 2.3.2 NLI noiseNLI noise is generated by interference caused by nonlinear interaction between signals. Since this noise cannot be measured directly, it is calculated using a physical model of signal propagation. When multiple wavelength signals are transmitted simultaneously through an optical fiber, nonlinear optical effects (such as the Kerr effect) cause signal interactions that degrade signal quality (Fig. 2, bottom right). This phenomenon is described using the nonlinear Schrödinger equation, and obtaining an exact NLI noise value requires solving this equation. Because the nonlinear Schrödinger equation has no analytical solution, two methods are commonly used:

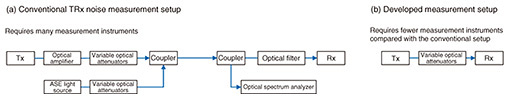

Simulations and real-world evaluations have confirmed that the approximate method achieves sufficient accuracy for metro and long-haul distances (hundreds of kilometers or more) [3]. NTT has verified using field-deployed fibers that this approximate method can also provide practically sufficient accuracy for NLI noise estimation in regions of around 100 km, assuming application to datacenter interconnects [4]. 2.3.3 TRx noiseNTT has developed two methods for estimating TRx noise: one for extracting TRx noise from TRx performance test data [5] and a simpler estimation method [6]. A TRx is a device consisting of electronic and optical circuits that converts electrical signals into optical signals for long-distance transmission. Commercial TRxes are designed with a balance of cost, performance, and power consumption, so the exact amount of noise they generate was previously unclear. Typically, TRxes undergo performance testing before shipment. In this test, ASE noise is externally added to the transmitted signal, and the bit error ratio (BER) is measured on the receiving side while varying the noise level (Fig. 3(a)). These test results are treated as performance data for the TRx. For example, a TRx with a lower BER at the same noise level is considered to have higher performance. By analyzing these data, NTT developed a method for extracting TRx noise and confirmed its effectiveness even for commercial TRxes [5]. However, this test requires many measuring instruments—such as optical amplifiers, an optical filter, an optical spectrum analyzer, and variable optical attenuators*8—making it costly and equipment-intensive (Fig. 3(a)). To address this, NTT developed a simplified method that uses only the TRx and a variable attenuator (Fig. 3(b)). With this method, the input optical power is varied using the attenuator, BER is measured, and the data are analyzed to estimate TRx noise. This simplified method has also been validated for commercial TRxes [6].

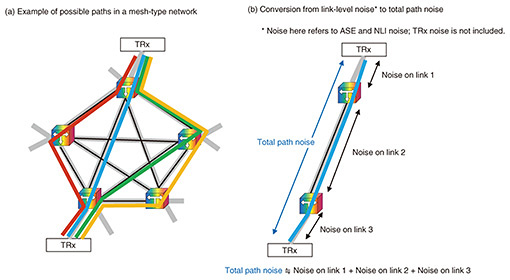

By independently estimating ASE noise, NLI noise, and TRx noise and summing them up, the total noise level of a transmission system can be determined. Comparing this total noise with the noise tolerance of each operational mode enables us to judge whether transmission is feasible. Finally, among the feasible modes, the optimal mode—based on conditions such as maximum data rate or minimum occupied wavelength bandwidth—is automatically selected and configured on the equipment. This completes automatic optical-path provisioning. 2.4 Efficient selection of the minimum-noise pathWe introduce NTT’s technology [7] for efficiently selecting the path with the minimum noise level from among numerous candidates. In the mesh-type networks envisioned for datacenter interconnects, a given source and destination can be connected via a vast number of possible paths (Fig. 4(a)). As mentioned earlier, transmission feasibility depends not on simple distance but on the amount of noise accumulated along the path. The lower the noise level, the higher the likelihood of successful transmission. However, calculating the noise level for every possible path is impractical because the number of paths increases exponentially with the number of nodes (reconfigurable optical add/drop multiplexers (ROADMs)). To address this, NTT proposed a method for first calculating noise at the link level (between ROADMs) then using these results to determine the minimum-noise path. With this method, the noise generated on each link (ASE noise and NLI noise) is treated as independent Gaussian noise, and the total noise for a path is considered the sum of link noise values (Fig. 4(b)). Once link-level noise is obtained, a shortest-path algorithm*9 can be applied to efficiently select the path with the minimum noise level.

This method was validated in collaboration with NEC and several overseas universities (Columbia University, Duke University, and Trinity College Dublin) using an academic testbed network in New York. The results confirmed that the total noise for the path can be accurately estimated from link-level noise values [7].

3. SummaryIOWN APN is expected to provide optical wavelength path services with ultra-high capacity, ultra-low latency, and ultra-low power consumption on demand, delivering the required bandwidth to the required location at the required time. To achieve this, NTT is working on using an optical-network digital twin to establish autonomous network operations. Focusing on automatic optical-path provisioning, this article introduced NTT’s efforts related to Design and Analysis, one of the three components of the digital twin loop: (1) Data Collection, (2) Design and Analysis, and (3) Control. For (1) Data Collection, NTT is developing technology to visualize the fiber-optic link efficiently [8]. For (3) Control, discussions on open interfaces for unified management of multi-vendor equipment are underway in standardization bodies such as IOWN Global Forum, OpenROADM, and Telecom Infra Project (TIP)*10 [9]. NTT will continue its research and development efforts in all three components of the digital twin loop to achieve autonomous network operation and truly on-demand optical services.

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||