Measuring the brains and bodies of top athletes during actual competitions

—Please tell us about the research you are currently conducting.

My specialty is the quantitative analysis of the characteristics of human cognition and behavior. I didn’t originally work in the field of sports; instead, I focused on hearing and multisensory perception. Since beginning to focus on sports about ten years ago, I’ve been conducting research in collaboration with top-level sports organizations and athletes.

Sports science is mainly related to the body in terms of exercise physiology and biomechanics, for example. In contrast, I’m focusing on the brain. Regardless of the excellence of a person’s body, it cannot function without the brain. Having said that, I believe that the brain cannot be treated in isolation. The underlying idea behind our sports research is that the essence of an athlete’s superior mental and physical skills lies in the interrelationship between their brain and body.

My ongoing research can be divided into two themes. One is research into the “technique” component of the three qualities of an athlete, i.e., mind, technique, and body (or strength). In other words, it deals with the mastery of skills. For example, when a batter hits a baseball, a huge amount of complex information is processed in the brain, and the movement of the entire body of the batter is controlled on the basis of information obtained through vision. Understanding the details of this information processing and identifying the strengths of top-level batters will reveal approaches to batting that differ from those that focus on power or form.

My other research theme concerns the “mind” component. In other words, mental strength. We often hear stories about athletes performing well in practice but failing under pressure during the actual event due to nerves. Conversely, we also hear about athletes entering “the zone” during the actual performance and demonstrating unexpected strength. If we could comprehend the neuroscientific mechanisms involved in the brain and body—not just mental attitude—during these moments, we might be able to create these ideal states systematically.

In conducting this type of research, we place importance on the reality of the experimental situation. Whenever possible, we conduct measurements during actual matches or similar situations. Before we focused on sports, we also conducted experiments under controlled, simple conditions. This approach is typical in basic research, and although it can produce precise results, it is not guaranteed that the knowledge gained can be applied directly to complex, real-world situations. Although it is difficult, one of my motivations for entering this field was the desire to take on the challenge of understanding what is actually happening.

Reality applies not only to the experimental environment but also to problem setting. Rather than creating fictitious problems for research purposes, we try to find research topics among the problems faced by athletes and teams. Of course, we filter our findings to see if they are novel from a cognitive-neuroscience perspective and whether they are suitable for analysis, but we want to feed the results back to the athletes. Their livelihoods are at stake, so a paper that shows a significant difference (statistical significance) in isolated factors but a small effect size (lacking practical significance) is meaningless.

We were latecomers to the field of sports, and our research in this field was a constant process of trial and error. After ten years, however, we have somehow managed to establish our own research approach, even when viewed from a global perspective.

—It is difficult to accurately measure vital signs on-site at a sports event, correct?

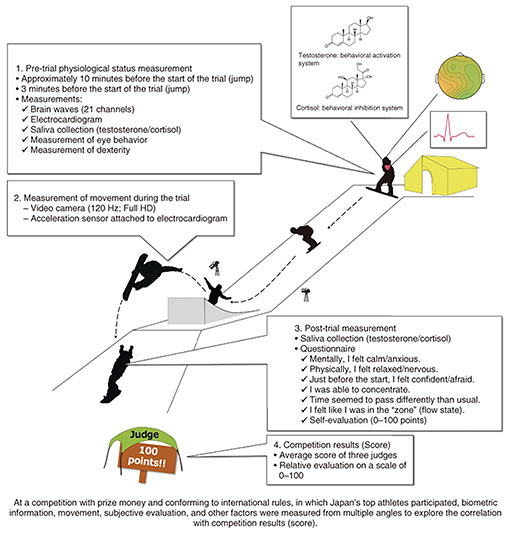

Since measurements are taken during competition, it would be counterproductive to disturb the athlete in question and cause them to fail. For that reason, we strive to make thorough preparations in terms of, for example, ensuring that the measurement team operates the equipment skillfully, selecting measurement methods that do not interfere with the athlete’s performance, and checking the quality of the measurements. However, on the day of the sports event, the conditions often turn out to be more severe than expected. For example, during measurements at a Big Air snowboarding competition (Fig. 1), we had to quickly set up the measurement tent ourselves in the middle of a snowstorm after the tent company refused to provide one.

Fig. 1. Example of measurements taken at a Big Air snowboard competition.

A decent neuroscientist would say that it is impossible to measure multiple parameters, such as brain waves, heart rate, eye movements, and salivary hormones, of over 20 competitors simultaneously in such an environment. Even if we only look at brain waves, anyone with an electroencephalograph can measure some kind of signal, but that signal alone is mostly noise. To measure and analyze at a level of quality that can be published in a scientific journal requires considerable expertise, and it is unlikely that such expertise is readily available anywhere in the world.

It is now common to use computer-vision technology to capture motion from video footage; however, standard methods cannot capture the movements of snowboarders performing spectacular tricks in the air. That is because snowboarders’ movements are complex and their clothing tends to be baggy. Part of our research is developing measurement methods for obtaining reliable data for any sports, not just for snowboarding, under harsh conditions. Above all, it is important to build strong relationships of trust with top athletes so they will actively cooperate with us.

—Would you also tell us about measurements in other sports?

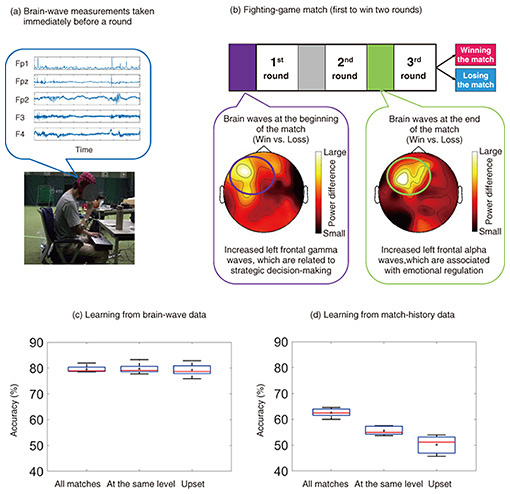

For e-sports, we simultaneously measured the brain waves of both advanced fighting-game players during a one-to-one match. The measurements indicated that the outcome of the match is already decided—to a certain extent—in terms of brain state of the two players just before the match begins. When we examined the players’ brain waves in the eight seconds just before the match (Fig. 2(a)), we found that the areas of activity in the brain differed significantly when the player went on to win or lose the match (Fig. 2(b)). Therefore, when we used machine learning to predict the outcome of the match from this brain-wave data just before the match, its accuracy was approximately 80% (Fig. 2(c)).

Fig. 2. Pre-fight brain activity can predict victory or defeat: an analysis of fighting games.

It is important to also be able to predict “upsets.” Today, with the rapid spread of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning is being used to predict the outcomes of various games; however, these predictions are basically based on past match history. This approach makes it fundamentally impossible to make predictions that deviate from past match history. With our method, however, the accuracy rate does not decrease even with an upset. Our method still achieves 80% accuracy in predicting that the weaker player will win the next match. By using the latest biological information about the players, such as what their brains are like just before a match rather than what their past results have been, we can predict outcomes more accurately.

While this research focused solely on the brain, we are also conducting research that focuses on the relationship between the brain and body. In collaboration with members of the Japan Rifle Shooting Sport Federation, which includes Olympic athletes, we are analyzing the relationship between high and low scores in air-rifle competitions and the state of the brain and body. During such competitions, competitors fire 60 shots within 75 minutes and compete for the highest total score. The outcome is decided in millimeters from a distance of 10 meters, so it is a sport in which athletes must remain extremely still to the point that one wonders, “Can people really be that immobile?”

In this study, we measured various biological signals from the whole body, including brain waves, heart rate, and breathing, and analyzed the relationship between those signals and the score. As the paper has not yet been published, I will refrain from going into details, but I will say that we have made a discovery, namely, the relationship between the brain and heart significantly influences the score. Although the relationship between the brain and heart is a hot topic in the field of neuroscience, our research focuses on parameters that completely differ from those of previous studies.

It is interesting that the athletes are unaware that such things are happening in their brains and bodies. One top shooter told me that when they are in top form, they feel like they are “pulling the trigger without even realizing it.” Shooting may thus be precisely the kind of activity that corresponds to that state. From the outside, it may appear that the shooter is motionless, but dramatic changes are occurring inside them.

The eyes tell the story of the brain

—Would you tell us about your research into eye behavior?

The eyes are sensors for seeing, but eye behavior, such as gaze, blinking, and changes in pupil diameter, also changes in response to cognitive information processing in the brain. Starting from the laboratory level, we have been continuously researching the relationship between such eye behavior and the brain’s (cognitive) state.

One example of our research that applied this relationship to actual sports competition is the measurements we took during the Super Formula Championship, Japan’s highest level car race. Contested at top speeds exceeding 300 km/h, this race is a fierce battle in which results are decided by differences of less than a second after dozens of laps around the circuit. Since the performances of the race cars do not differ, the driver’s skill and team strategy play a major role, and split-second decisions, such as whether to take a risk and overtake, are the key to victory.

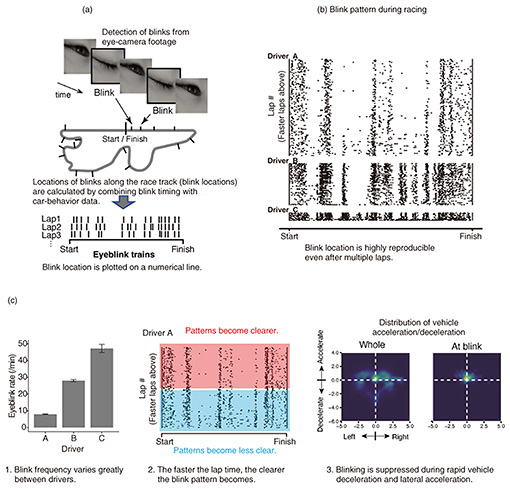

We want to objectively capture changes in the driver’s internal state, such as their judgment and concentration, but measuring brain activity during a race is difficult; therefore, we focused on blinking. Athletes blink unconsciously, but the frequency and timing of their blinking may reflect the state of their brain. When we measured blinking using a small camera embedded in the driver’s helmet, we found a surprising regularity in their blink patterns.

The locations along each lap of the track at which each driver (A, B, and C) blinked are shown in Figs. 3(a) and (b). Although some individual differences can be seen, all three drivers blinked at similar locations, and that finding indicates high reproducibility within individual drivers. Further analysis revealed three factors that produce these blink patterns (Fig. 3(c)).

Fig. 3. Exploring cognition and brain states through the eyes: Experiments during a Super Formula race.

The first factor is the difference between individual drivers, i.e., some drivers blink more and some blink less. Regardless, they are all top-level drivers and blink frequency has no bearing on performance. The second factor is the speed of the lap, i.e., the faster the driver is “attacking” (that is, the higher the risk and concentration), the more defined the blink-timing pattern becomes.

The third factor is vehicle acceleration. If vehicle acceleration in the longitudinal and lateral directions is plotted over the entire journey, a heart shape (in green) like the one in the left plot appears. The graph on the right shows the vehicle acceleration only when the driver was blinking, and the green plots are concentrated around the origin (zero acceleration). In other words, blinking is suppressed when the driver is cornering or braking hard. This finding may also be related to risk and concentration. Although much about the brain mechanisms behind the above-described phenomena remains to be explained, I believe that in the future, it may be possible to estimate brain state from measurable information even in harsh environments.

Incidentally, we also measured biological information other than that concerning the eyes in this race. One of those measurements concerned hormones, i.e., cortisol and testosterone, the levels of which we measured by collecting saliva from athletes before and after a race. Cortisol is a type of adrenal cortical hormone that acts to counteract stress. It has been suggested that it is related to brain activity that increases anxiety and inhibits certain behavior. Testosterone is a type of male hormone that is thought to be related to brain functions that increase aggressiveness and proactiveness and promotes certain behavior. These hormones may be involved in risk-taking and aggressive behavior.

Our analysis showed that the balance of these hormones is related to race results; the interesting finding was that the hormone that is more strongly related to performance varies from driver to driver. If we think further about this finding, it makes sense. That is, drivers who tend to take on risky challenges would be better off not taking any more risks. On the contrary, drivers who are overly cautious may perform better by taking more risky actions. If we can objectively understand the type of driver in this sense, we may be able to make interventions that are tailored to the driver type.

Returning to the topic of eyes, we previously published a paper stating that eye behavior during baseball batting depends on skill level. No matter how much power a player has or how fast their swing is, they will not generate ball speed unless the ball makes solid contact with the sweet spot of the bat. Hitting the ball on the sweet spot requires accurate prediction of where and when the ball will land, and the quality of the visual information that forms the basis of that prediction depends on eye behavior. This study can be seen as an attempt to estimate the predictive ability of a batter’s brain from the eyes. The content of the paper is apparently already being used by Major League Baseball teams in North America. We have accumulated more data in Japan. At the spring training camp of a certain professional baseball team, almost everyone—from first-string stars to developing young players—was measured all together.

After accumulating this kind of data, we can use it to develop and evaluate players. There are many different types of “good batters” in terms of their physiques, physical abilities, playing styles, and other factors that vary considerably, and all have different goals to aim for. Eye behavior provides valuable clues for determining a player’s type and identifying areas that should be developed for each player.

Eye behavior may also be useful in identifying a player’s current and future potential. Among the players we measured was a star player with ideal eye behavior. Although he was of small stature and didn’t have a fast swing, his power hitting was top class. Several young players displayed eye behavior similar to that of the aforementioned star player. They have yet to achieve any notable results, but with the right amount of experience, they may become as good as the star player. Conversely, one player was drafted as a first pick but struggled to make it to the first team and eventually quit. Although a problem with his eye behavior was evident from the start, we cannot say for sure that it was the reason he was unable to perform well; even so, it was entirely predictable that he would struggle against high-level pitchers.

As I mentioned earlier in my discussion about fighting games, using biological information such as brain and eye data—rather than past performance—may make it possible to predict future outcomes even when environments change. Such prediction goes beyond simply picking promising players; it can also help pinpoint the root causes of problems for athletes facing difficulties and discover improvement methods tailored to individual aptitudes and styles.

In search of the principles of optimization of the brain and body

—Please tell us about your future prospects.

In the field of sports, we have discovered several interesting phenomena unique to real-life situations concerning top athletes of several sports. Many were quite unexpected and still present many mysteries. In the future, we want to first focus on delving deeper into the neuroscientific mechanisms behind these phenomena. When providing feedback to athletes in the field, rather than simply saying, “If you do this, this seems to happen,” we should give such feedback after understanding the principles and mechanisms, thus make it possible to provide appropriate methods on the basis of individual characteristics and circumstances. Even if different athletes face the same problem and have the same training goals, it is often the case that different athletes should do completely opposite things. Of course, we want to publish our research results, but to ensure quality, I believe it is our responsibility to establish a solid foundation as basic research first.

I also want to focus on slightly different aspects of sports. One aspect is the interactions between multiple people. In sports, players play against each other, and sometimes they play with teammates. Simply gathering strong players does not necessarily make a strong team, and a team may perform well against some opponents but struggle with others. Momentum of the team can also affect individual performance. I want to unravel the true nature of this team-and-player-related phenomenon from a cognitive-neuroscience perspective. Observing this phenomenon in actual games will be more difficult than the challenges faced in my previous research, but the challenge is worthwhile.

Another aspect that I’m interested in is the neuroscientific mechanisms of beauty, emotion, and feelings. However, it presents a somewhat high hurdle. The aspects that I’ve dealt with up until now have quantitative results with clear “good” and “bad” and “win” and “lose” meanings. However, aspects such as “beauty” are subjective and perceived differently by different people. Our specialty is objectively measuring and analyzing brain and bodily reactions that the person may not even be aware of, but how can we make use of this skill or seek out new approaches? As part of that challenge, I’ve recently been expanding my scope to include music.

Our research has thus far been limited to top athletes, but we have our sights set on the activities of all kinds of people. Problems related to optimization or malfunction of the brain and body are present everywhere in everyday life, not just in sports. For instance, I recently injured my lower back and had difficulty walking. In terms of not only the direct inconvenience but also mental aspects, this injury alone caused a greater decline in my quality of life (QOL) than I had imagined. Walking around town with this perspective in mind, I noticed many more people than I expected who seemed to be having similar problems. As the population ages rapidly, these types of problems will likely become even more serious. Having experienced the symptoms myself, I feel that even symptoms such as lower-back pain and difficulty walking are often not simply caused by localized damage but by problems with the overall function of the entire body and brain.

I’m also concerned with the physical functions of children, who will be responsible for Japan’s future. In urban areas, there are fewer environments where young children can play using their whole bodies on a daily basis. We live in an age in which children even have to go to cram school to learn how to run. This state of affairs may have unexpected effects on cognitive and mental health. Even if it will take some time for these effects to become apparent, I’m a little worried.

Even in the age of AI, keeping the mind and body in good condition and being able to control them at will is the foundation of QOL, and I hope that our research will contribute to this goal.

The research topic teaches us the way

—Please tell us about your thoughts on pioneering your research field, what you keep in mind on a daily basis, and your message to future generations.

I’m not sure if what I’m about to say is a good thing or not, but my principle of action is very simple: I pursue interesting and mysterious things. As the proverb goes, “The child is father of the man,” perhaps it’s a remnant of growing up in the countryside, unaffected by entrance-exam studies and the like, where I single-mindedly pursued interests unrelated to school studies. Since I pursue research as a profession, I naturally think about its social significance. In that case, I think it will ultimately be more useful if I don’t become too short-sighted.

When conducting research, what you want to know or achieve should come first, and methodology should follow. It can be said that fields with established methodologies are no longer new. Taking on new challenges inevitably requires that you first create a method. It is also something that comes naturally to me personally. In fact, from a young age, no matter what I did, I never had anyone teach me; I just pushed ahead in my own way. I think that this approach caused me a lot of pain, though. I encourage young people to avoid being too clever and face essential challenges in their own way through trial and error. Instead of having someone teach you, let the phenomenon you are studying itself—even the tough parts—teach you.