Achieving optical transmission with higher capacity over longer distances by using existing infrastructure

—What type of technology is coherent optical-amplifier-repeater transmission?

Before explaining my research, let me provide some background on the evolution and changes in the basic transmission methods used in optical communications. Current transmission and communication via optical fiber uses light with wavelengths in specific wavelength bands. These light wavelengths are classified by band and referred to in order of shortest wavelength as the S band (short band), C band (conventional band), L band (long-wavelength band), and U band (ultra-long-wavelength band). Currently, the C and L bands are primarily used for high-capacity, long-distance communications because these two wavelength bands enable efficient data transmission with little attenuation or distortion, which is the fundamental characteristic of optical fiber occurring over the transmission distance.

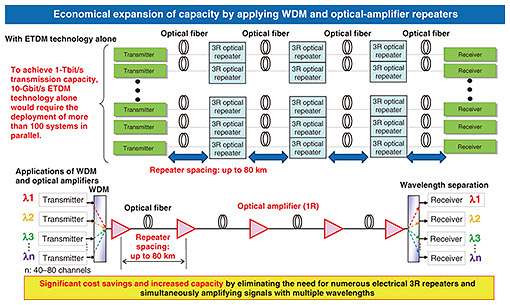

NTT completed a fiber-optic-cable network encompassing Japan in 1985. At that time, 3R (regenerate, reshape, retime) repeaters were installed at regular intervals (approximately 80 km) across the network. A method called regenerative repeating was used to convert an optical signal to an electrical signal at the repeater, where the electrical signal was reshaped, amplified, then re-transmitted as an optical signal. With this method, digital data (as 0s and 1s) are assigned to the “flickering” (i.e., switching on and off) of light, and communication capacity was increased by upgrading the transmitters, receivers, and repeaters to use a technology called electrical time-division multiplexing (ETDM), which increases the flicker rate. However, to keep up with the aforementioned rapid increase in communication volume, a large number of optical devices, such as transmitters, repeaters, optical fibers, and receivers, are required. For example, to achieve a capacity of 1 Tbit/s, it would be necessary to set up 100 parallel 10-Gbit/s ETDM-based systems. To economically increase the capacity of optical transmission systems, optical-amplifier repeaters and wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) were introduced in the late 1990s (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Overview of a transmission system using optical-amplifier repeaters.

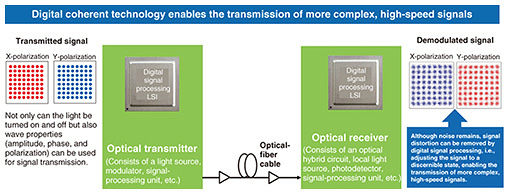

These two technologies make it possible to bundle signals of approximately 40 to 80 different wavelengths (i.e., wavelength multiplexing) and transmit them in parallel over a single optical fiber. Optical amplifiers can amplify and transmit wavelength-multiplexed optical signals as light (i.e., without converting them to electrical signals) in a way that enables economical high-capacity, long-distance communications. In response to the explosive growth of the Internet and mobile phones, digital coherent technology was introduced in the early 2010s to further increase capacity. With this technology, the transmitted optical signal that undergoes dynamic changes and distortions as it passes through the optical fiber is digitally corrected using a signal processor (LSI: large-scale integrated circuit) installed in the transmitter and receiver. In contrast to the conventional method of simply flickering light on and off, digital coherent technology enables the use of advanced signal formats that use the wave properties of light (amplitude, phase, and polarization), and it makes it possible to transmit high-speed optical signals at speeds exceeding 100 Gbit/s per wavelength (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Mechanism of digital coherent technology.

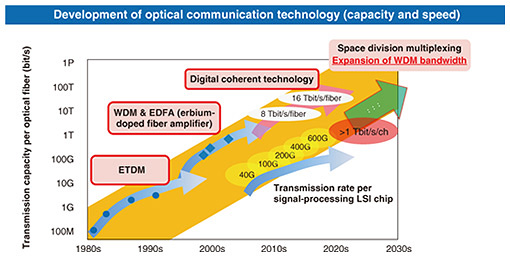

More than 40 years have passed since 100-Mbit/s transmission systems were introduced in the early 1980s, and transmission capacity per optical fiber in backbone networks has increased by more than 100,000 times to over 10 Tbit/s. Following the 1980s, when it was only possible to send text data, it became possible to send pictorial symbols (of about 12 × 12 pixels) along with the text then images such as cell-phone photos. Today, even large amounts of video data can be sent. While ordinary users rarely have the opportunity to see these advances, I believe many have experienced the increase in capacity indirectly (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Transition of optical transmission technology.

With the ongoing emergence of new Internet services and the increasing performance of mobile devices, it is predicted that communication volume will continue to increase at an accelerating rate. Under these circumstances, research into digital coherent systems using the existing C band and L band has progressed significantly, and advances are being made to the point that the theoretical limits of capacity are becoming apparent. In preparation for this further increase in communication volume, space division multiplexing and WDM bandwidth expansion are being researched. WDM bandwidth expansion aims to increase communication capacity by wavelength multiplexing in the S band, which covers shorter wavelengths than those in the C band, and the U band, which covers longer wavelengths than those in the L band and has been thought to be difficult to use due to the characteristics of single-mode optical fiber. However, it presents several major challenges. It becomes necessary to develop transmitters/receivers and optical-amplifier repeaters that support new wavelength bands; for certain bands, some components require reconsideration at the material level. From the U band to longer-wavelength bands, significant attenuation occurs due to the characteristics of silica glass (the material used in optical fibers). As the number of wavelength bands used increases, the energy transition between wavelength bands caused by the nonlinearity of optical fibers becomes non-negligible, which makes it difficult to transmit signals with uniform signal quality in each wavelength band.

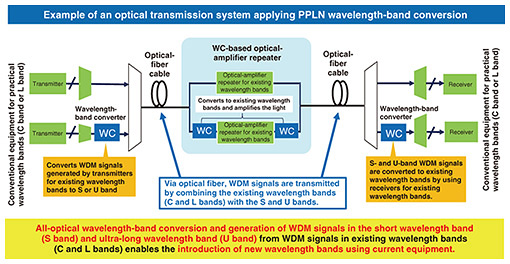

Finally, I want to talk about my research. To solve the problems that I mentioned above, I’m considering applying an optical signal-processing technology called wavelength-band conversion, which takes advantage of the wave properties of light (so-called coherency). This technology uses NTT’s proprietary, highly efficient optical device called a periodically poled lithium niobate (PPLN) waveguide, which simultaneously converts multiple optical signals into different wavelength bands in a way that retains their optical properties. This conversion technology enables the transmission and reception of U-band and S-band WDM signals via optical-amplification relays by using current C-band and L-band wavelength-band equipment. It also makes it possible to increase the wavelength-multiplexable bandwidth by using existing optical fibers and repeaters, achieving even greater capacity (Fig. 4). To address the issue of energy transitions between wavelength bands, NTT has independently improved simulation technology based on theoretical models; thus, it is now possible to optimize signal-transmission conditions, such as power transitions that occur when wavelength bands are expanded.

Fig. 4. Expanding wavelength resources using PPLN wavelength-band converters.

In March 2024, we applied the above technologies to achieve a high-capacity, long-distance optical-amplification transmission of 100 Tbit/s over a distance of 800 km by using three (C, L, and U) wavelength bands. In March 2025, in addition to expanding the S, C, L, and U bands, we expanded the wavelength band to the even-longer-wavelength region of the unnamed U-band (proposed to be named the “X band”) and experimentally demonstrated 160-Tbit/s transmission over 1000 km—even greater capacity and longer distance. These advances in transmission were not made possible solely through completely new technologies; rather, they were achieved through the accumulation of previous technological breakthroughs concerning ETDM, WDM, optical amplifiers, digital coherent technology, and current WDM bandwidth expansion, including wavelength-band conversion. The fusion of these technologies results in the coherent optical-amplifier-repeater transmission technology that I am now researching.

—What difficulties did you face in this research and what challenges do you face from now onwards?

Research into optical transmission systems involves communication with a wide range of people, including researchers specializing in a wide range of underlying technologies (such as components, equipment, optical fiber, and digital signal processing), equipment vendors, and even network operators. Under such circumstances, it is necessary to persuade people to acknowledge the effectiveness and necessity of expanding current wavelength bands to new wavelength bands. Persuading them is no easy task, because it has been the established view that we should use the C band or L band for optical transmission since it is optimal in terms of the ideal optical-fiber characteristics. There have also been no examples of practical optical transmission systems using optical signal processing such as wavelength-band conversion. In academia, the need for wavelength-bandwidth expansion has been logically explained through conference presentations, papers, and other means. However, to introduce wavelength-bandwidth expansion into actual optical networks, we need to propose the application of a new wavelength band and get it adopted in an environment in which mature operations and ecosystems based on transmission in the C band and L band have already been built; we are currently struggling to achieve this.

WDM optical transmission technology that applies new wavelength bands is currently at the stage where we have been able to demonstrate its principle in the laboratory. Regarding wavelength-band conversion, which is an important elemental technology, we are currently striving to establish long-term reliability, and I believe it is important to clear the necessary hurdles one by one steadily and quickly in a manner that leads to practical application while promoting the usefulness of the technology.

Combining WDM bandwidth expansion + PPLN wavelength-band conversion with space division multiplexing to expand new horizons

—Please tell us about your future prospects and goals for WDM optical transmission technology that applies new wavelength bands and wavelength-band conversion technology.

The transmission distance that we are experimentally verifying (800 to 1000 km) is sufficient to cover the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka route, which currently has the highest network traffic in Japan. First, we want to apply WDM bandwidth expansion as a technology that will contribute to increasing the capacity of this route. I believe that it may be possible to use wavelength bands longer than the X band and bands with wavelengths shorter than the S band (e.g., O (original) and E (extended) bands). In the IOWN (Innovative Optical and Wireless Network) initiative promoted by NTT, the actualization of petabit-class link capacity in the underlying All-Photonics Network positions WDM bandwidth expansion, together with space division multiplexing technologies, as key enabling technologies, and the integration of these technologies is essential. I also believe that increasing the number of wavelength bands (wavelength resources) that can be used through wavelength-band conversion technology will significantly contribute to establishing flexible networks that use abundant wavelength resources.

—What led you to join NTT?

In 1997, I was at an NTT-sponsored music concert by a certain band and saw a commercial for NTT’s Phoenix System. In the commercial, the band members were using the system to make video calls via a personal computer to elementary- and junior-high-school students in a remote location. At that moment, I first became aware of NTT. I also heard that audio data were being sent from Los Angeles to a studio in Tokyo via multiple ISDN (integrated services digital network) lines, and I was amazed at the potential of communications technology, which sparked my interest in communications. Influenced by that band, I became interested in synthesizers, and since I wanted to work in a field related to digital instruments, I went on to study applied physics at Waseda University.

During my high-school and university years, in addition to music, I enjoyed playing online games over the Internet, so I was not completely unconnected to the rapidly advancing and developing world of communications. Initially, I vaguely thought it would be suitable to get a job at a company that manufactured digital musical instruments; however, when I actually started thinking about finding a job, I had doubts about turning my hobby of music into a career, so I set my sights on communications, which I was equally interested in. For that reason, I joined a research lab at the graduate school of the university that focused on high-capacity optical-fiber communications. As I researched the latest trends in optical-fiber communications at that laboratory, I was overwhelmed by NTT’s research results. I therefore decided that NTT would be my first choice for employment. In 2006, I expressed my desire to research high-capacity optical-fiber communications and was able to join NTT and was assigned to the department of my choice. I continued my research career in that department for over 10 years, working on high-capacity, long-distance optical transmission technology and optical access networks, and received a Ph.D. in engineering in 2019. I am currently continuing the research and development of high-capacity, long-distance optical transmission technology.

—What do you consider important when conducting your research?

I keep two things in mind as a researcher: reach the first milestone and anticipate one step ahead of what you imagine and act accordingly. Specifically, I believe it is important to be the first to reach an area that no one else has explored. Naturally, many researchers worldwide are doing the same research, so I think it is important to assume that your goal will also be theirs and take a two-tiered approach with your goal set higher than theirs. This approach will increase your chances of reaching the first milestone.

Speaking of approaches, I always keep in the back of my mind the words of the director of NTT Network Innovation Laboratories when I first joined the company, “It is fine to aim to be the first to reach the summit, but make sure you don’t climb the wrong mountain!” In my specific field of research, this metaphor means that although my ultimate goal (the summit) is to achieve both high capacity and long distance, pursuing only one or the other would be like climbing the wrong mountain.

—Please tell us about NTT Network Innovation Laboratories, where you currently work.

The mission of NTT Network Innovation Laboratories is to dramatically improve the performance of communications technology, pioneer new areas of use, and lay the foundation for practical application in accordance with our basic philosophy of “making previously impossible services and societies possible by utilizing high-capacity communications technology.”

We have a department that conducts research on transmission systems for the physical layer of optical and wireless communications as well as a department that conducts research on higher layers covering networks and communications systems. These departments pursue a wide range of research and employ specialists in a variety of fields, so we can pursue high-level research and development in collaboration with each research group. As a long-established laboratory, we have a wealth of research knowledge, and being an environment equipped with cutting-edge facilities, it is an easy laboratory to work in.

—What is your message to students and other researchers?

To students, I believe that rather than getting caught up in whatever research is trendy at the time, you should pursue what you genuinely want to do. Research that has already been published and gained attention is often practically finished, and the competition inevitably becomes fierce. Research in fields currently out of favor could come back into the spotlight at any time. If you’re the only one pursuing that research, you’re the only one who can step into the spotlight. In terms of being the first to reach a milestone, it is crucial to identify what you truly want to do without being swayed by trends.

Although my specialty is high-capacity optical-fiber transmission, when I was a student, I had many friends who were researchers in completely different fields and with backgrounds such as mathematics and astronomy, and some are now involved in the same research as me. So if you are interested in optical communications, even if your current research is in a different field, I’d love to work with you at NTT.

To those of us working together on research and development of optical communications, I believe that the field of optical communications is currently one of Japan’s technological strengths, so I hope that we can continue to raise our technological levels together—not only through competition but also by cooperation—so that we can continue leading the world.